Storytelling works! No surprise, didn’t we go to sleep as children only after hearing a story? Today, if we remember experiences from the past, we automatically fabricate our own stories. Storytelling moves not only the head, it also moves the heart, our emotions. Thus, can storytelling be a method for critical education? We suggest: Just to put a message into the form of an exciting and thrilling story does not yet suffice for a method that supports critical thinking. But stories offer entry points for critical learning.

Why is storytelling a powerful tool?

Two scenarios:

Scenario 1: Expert Eric explains the increase in precarious labour relations and the effects on society by means of painstakingly collected figures, data, statistics.

Scenario 2: Speaker Samantha describes the same facts by telling the story of Barbara Z. who works extra hours everyday and yet struggles to meet ends with her family of six. The small flat, the children who are on top of each other and fight constantly because there is not space enough, all that is part of the story.

We know the effect. If presented by Eric we struggle to grasp the subject matter although it is clear and well presented, it still remains abstract, alien and without great effect. Once Samantha packs the matter into a story, that changes. Empathy, excitement, maybe anger arise, the listeners feel with Barbara in her situation.

Not only emotions make storytelling a powerful tool. Stories were told to all of us when we were children. We remember stories, whether we want it or not. It is part of the development of each individual, but even more it is also part of the development of humanity at large.

In human history stories played an important role for passing on knowledge. It is an ancient „teaching method“ from times long before the establishment of schools, or the development of writing. During the Stone Age already children most likely listened to the adults telling fascinating hunting stories before the children ever took part in the hunt themselves. This trained and developed an „episodic memory“ in which stories, sequences, events can be stored effectively, and at any rate better than in an „abstract memory.“

Even master minds of mnemonics use the power of stories by packing facts and terms which they want to keep in their memory into a story. In this manner it is easier to retrieve the content.

Storytelling isn’t new at all – in spite of the „hype“ that is created around storytelling in recent years. The internet is full of offers and publications concerning storytelling. Why is that? Of course the effectiveness of storytelling is one reason, at the same time as a method it is easy to learn. And there is also the advertising where we are told glossy stories and heroic epics. Sure, we will use stories in adult education and all will be fine?

Stories and History

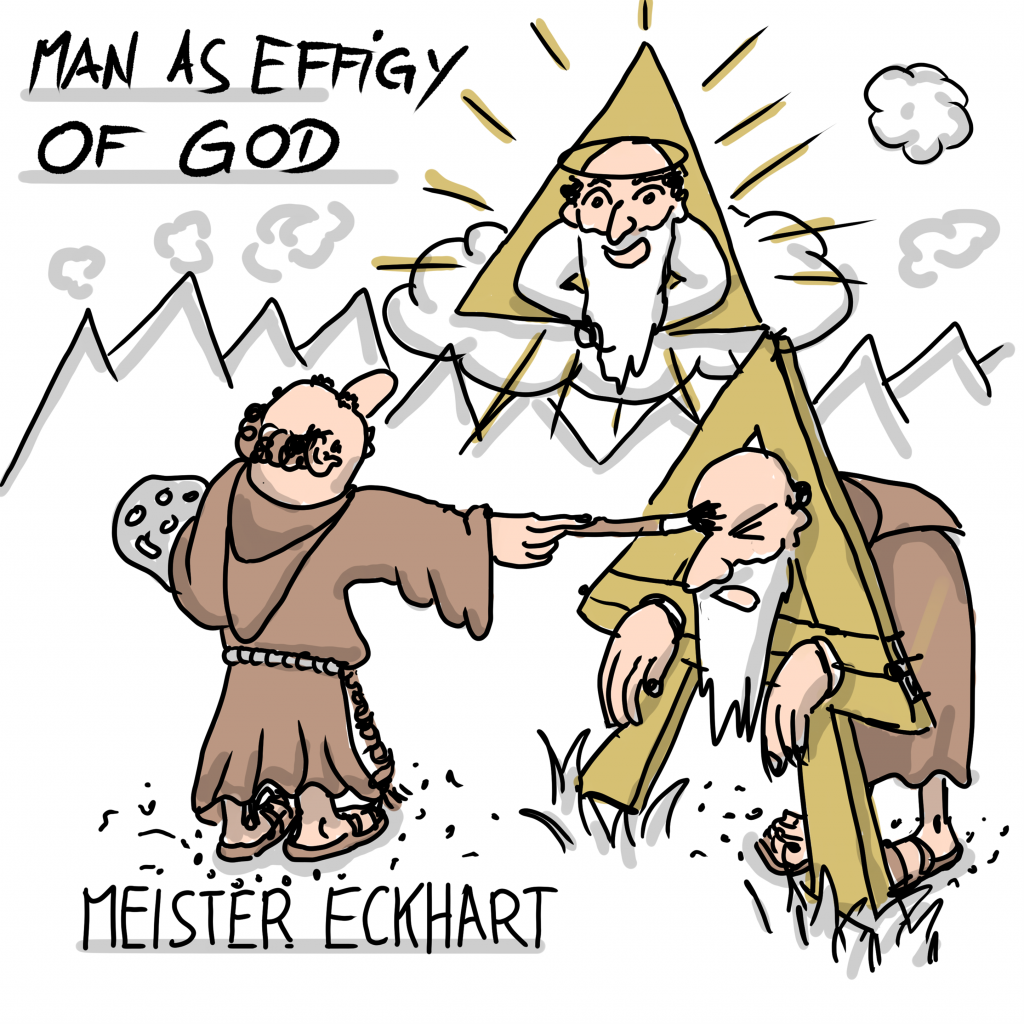

The concept of education as „Bildung“ originates in the middle ages. Humans were supposed to form as effigy of god, hence function as part of a big story.

The mega-story at the time was the bible. It was used to explain literally everything.

Bourgeois enlightenment however developed a critical concept of „Bildung“. Here the means used were sensuous experience, measuring, facts, methods of natural science; truth was no longer sought in the bible.

That does not mean there were less stories told. Quite the opposite. In the cultural struggle for domination in society elite education was meant to justify the bourgeois claim for power. Knowing the great mystical stories from ancient history became the status symbol of humanist bourgeois education, and a means of demarcation against the supposedly non-educated (aristocrats, peasants, workers).

For the working class movement during the 19th century─still illegal for long times─the everyday stories and songs of resistance were a starting point for a collective empowerment against the yoke of bourgeois domination. Books were rarely got, and if there were some, only few people could read them. The own everyday experiences and stories provided the basis for a critical appropriation of the world, also by learning to read, write and calculate.

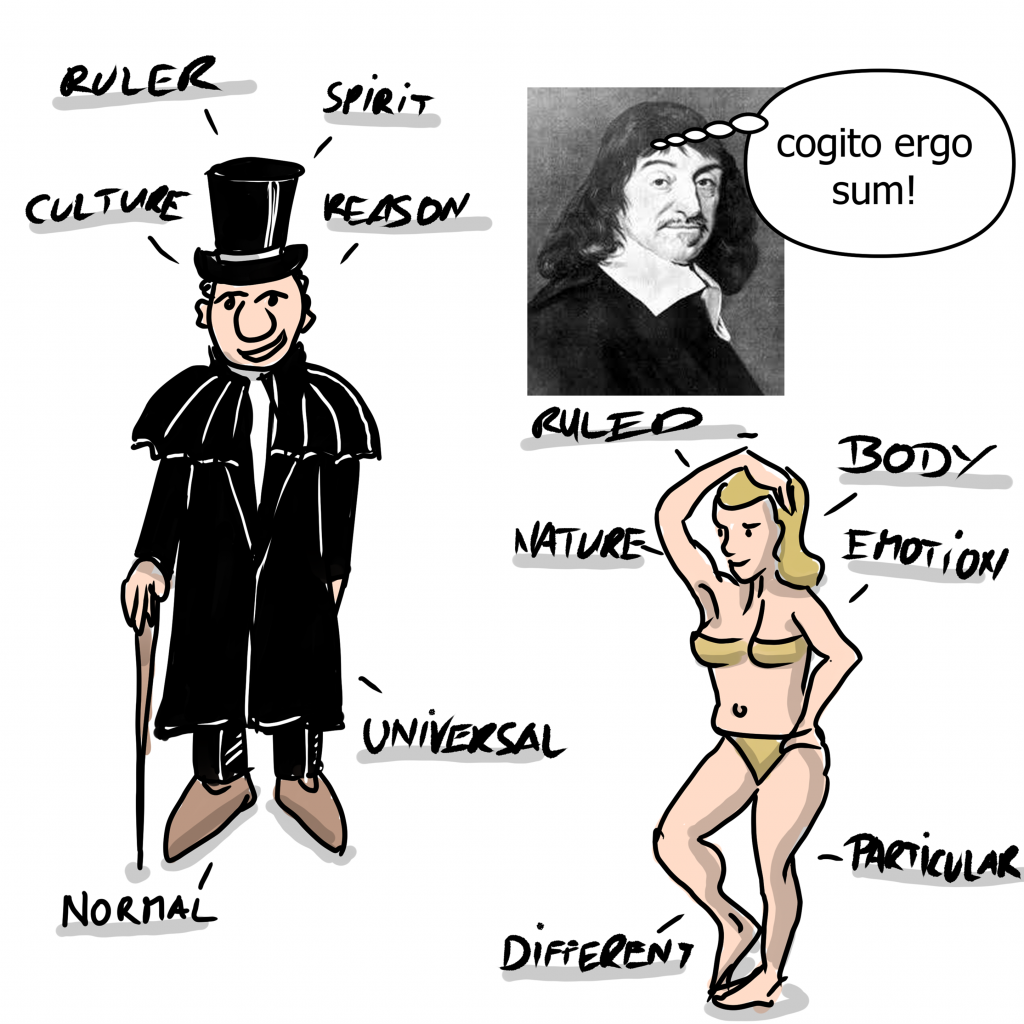

The feminist movement of the 20th century in turn criticised the bourgeois separation of society in a dominant masculine, rational, universal, spiritual world of culture and a subordinated feminine, emotional, mundane, physical world of nature.

As the knowledge of women was hardly valued feminists employed stories from everyday life to explicate a critical standpoint. Beginning with the own mundane stories rather than the grandiose male sagas male dominance was going to be studied and criticised „from below.“ These stories of the own life are a portal for a collective analysis and struggle against relations of domination.

The crux of truth and reality

In storytelling truth and reality are of minor importance. Stories are „didactically condensed.“ Punch lines and details in the stories are by times creatively made up for intended effects. Stories can connect learning processes with practical life experiences. But empirical evidence, they are not.

It is not a new achievement of the „post-factual politics“ with its fake news that stories are sometimes invented or tweaked. That was always the case when people told stories. There is the one of the Bavarian robber Mathias Kneissl who supposedly on his way to the guillotine─on a Monday─said to the executioner: „Well, that’s a good start of a week!“ A nice story for the common people with whom Kneissl supposedly shared his booty. He was beheaded on February 21st, 1902, which was a Friday. Like many other stories the tale of Kneissl is prone to building myths, for those the question of truth, or even more a critical perspective is irrelevant. For an old robber tale that may be entertaining. If we think of the stories that are circulated by the right about refugees, people of diverse sexual orientation, or people of colour … it is bitterly serious.

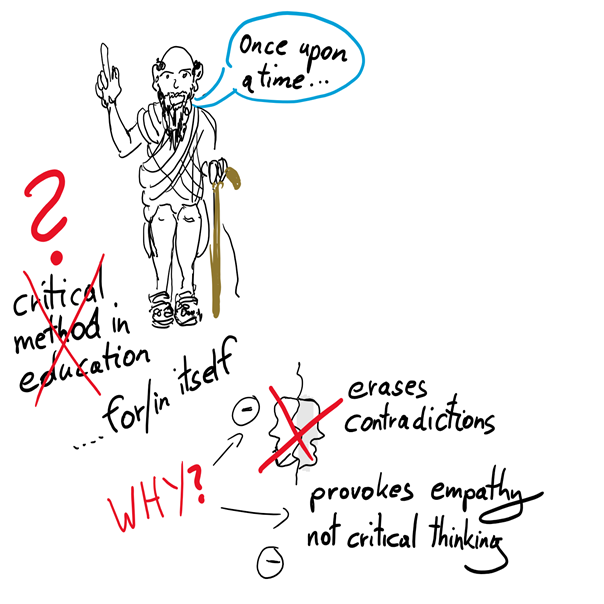

Storytelling ─ not a method for critical education!

Storytelling can be abused ─ this it has in common with other methods. In the first instance they are rather „tools“ that can be used for different purposes. But then there are specific characteristics for each method that make it more or less useful for specific learning objectives, as for example critical thinking and posing critical questions.

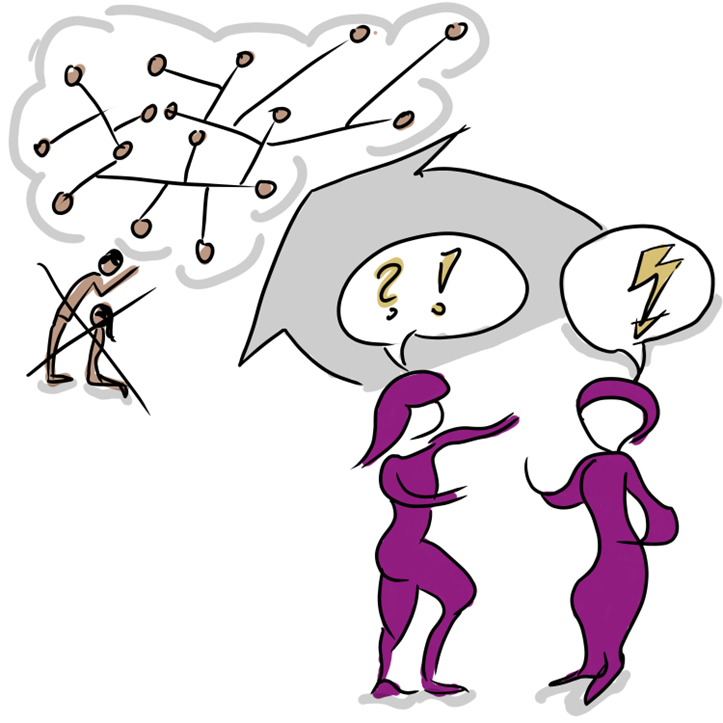

Critical thinking starts with contradiction. A good story blends out contradiction, stories need to be consistent for being effective. Whatever disturbs consistency is bend to fit and thus contradiction is erased.

Storytelling affects emotions, triggers empathy and identification. We put ourselves in the shoes of the „hero“ or in those of the adversary. We are straight in it. Critical thinking and education however need distance. A subject matter needs to be seen form an outside perspective, as an object, for being „appropriated“ in a learning process. What happens here? And most importantly: why? What are the contexts, the contradictions? How does it appear if I look at it from a different perspective?

Stories ─ used differently

Now one might say, storytelling cannot at all be combined with a critical notion of education and all we need to furnish is facts, facts, facts. Off the mark! For processes of critical education stories are indispensable, not because they are „authentic“, but rather engraved in our stories and memories are societal relations of domination, common sense ideologies and world views. Hence they provide a fabulous window for a critical perspective on the individual, the personal and the societal, and therefore our actions in the world. And there are in fact a lot of ideas and experiences how storytelling can be connected to the objective of „critical consciousness.“

Two examples:

1. Stories as entry point for learning processes

We activate participants and ask them to tell their story about a concrete experience they had themselves with a particular topic.

In our seminars this could be, for example:

| Topic | Trigger for the story… |

| Train-the-Trainer | The moment when I „got it“… |

| Solidarity | The moment when I experienced concrete solidarity… |

| Labour legislation | A time when I experienced the limits of law… |

| Racism | A moment when I caught myself… |

In this manner we put the topic into a relation with reality and lived experience of the participants (not an effigy!). At the same time emotions are evoked. But now the level of critical thinking is needed also.

For solidarity this can be questions like: What does solidarity mean for us today? Did that change, and if so, why? What are the public debates about solidarity (e.g. during Corona lock-down)? How can we enact solidarity in the workplace? And it could lead to the question towards the end of the learning process of: What story about solidarity do I wish to tell in the future?

The topic of racism also needs to be extended beyond stories. That entails─besides an analysis of societal conditions for latent racism─a self-critical questioning: How much racism do I carry inside me and where does it come from?

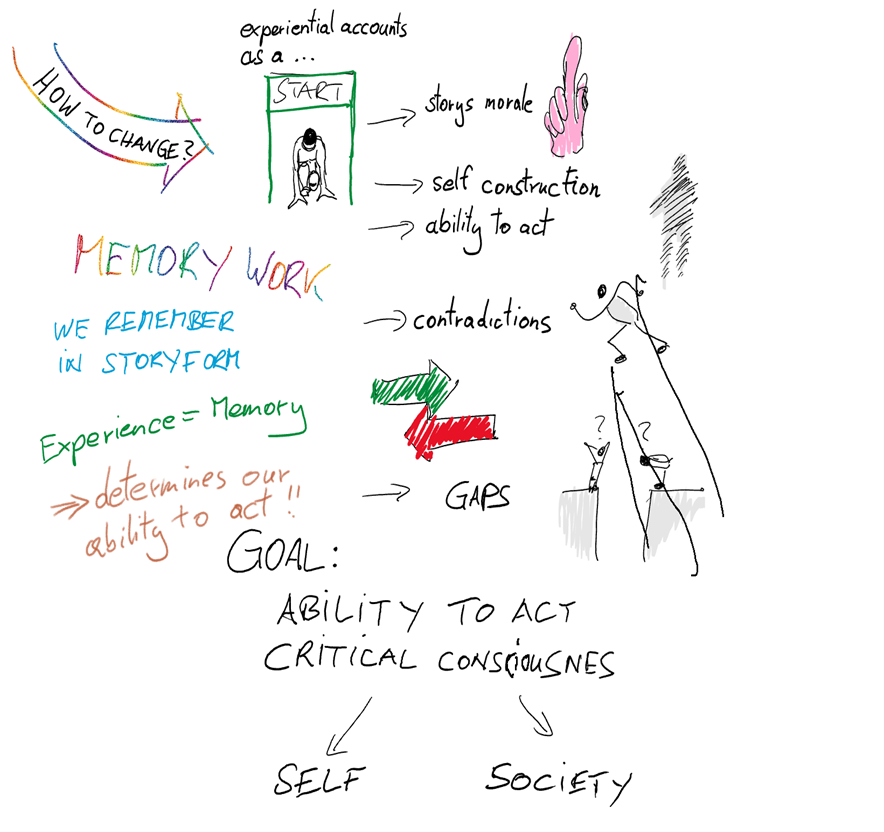

2. Stories as material for Collective Memory-Work

In the feminist movement the format of Collective Memory-Work was developed. Here stories are of central importance. Stories written by participants are used as material for an extensive process of working and learning together:

- Step 1: The group agrees on a topic, e.g. „That annoyed me in the course…“

- Step 2: Everyone writes a page (A4) about a particular situation that they relate to the topic.

- Step 3: The story is re-written in third person narrative. That creates distance. From this moment on the group works with the text to investigate societal relations; it is not an analysis of a particular person.

- Step 4: Everyone reads out their story to the group and collectively one of the stories is chosen for a first analysis.

- Step 5: The story is analysed by using the following questions:

| 1. What does the author want to tell us ? („… and the moral of it is?“) |

| 2. How can we express the author’s message in a proverb? |

| 3. What other well known fairy-tales, stories, films, myths… come to our mind? |

| 4. How are the persons in the story described (e.g. passive, active, visible, invisible, direct, indirect, acting/suffering…)? |

| 5. What is missing in the story that would be needed to make it work in reality? (Voids) |

| 6. What contradictions, what fields of tension arise? |

| 7. How are individual action and societal relations interlinked here? |

| 8. After finishing the analysis: What is the (new) message that the text contains? |

| 9. What theories and scientific insights exist on it? |

| 10. How would the story have to be revised for increasing the actors‘ capacity for action? |

Tips to think further

We know that storytelling can lead to the spread of messages that we do not wish to spread at all. Nevertheless in our seminars we like to use the “Storypower” (a book by Vera F. Birkenbihl) because there are few other methods that create similarly sustainable learning.

Making use of stories beyond the simple reaffirmative story-telling only is also part of other trade union education programs. For example, with the scenario-technique ideas for possible „futures“ can be developed. We don’t leave this to the corporations only. The scenarios of desirable future/s become alive by way of stories. The Hans Böckler Stiftung has developed four scenarios of digital futures and the role of trade unions in adult education. Sascha Meinert and Michael Stollt explain scenarios:

Frequently, we have a limited view of the future and our options for affecting it. All too often we are overwhelmed by haste and multifarious everyday demands, a narrow view of the evidence and the mere extrapolation of current trends. Only when people’s backs are up against the wall does anything get done and even then only reactively and under pressure. Using scenarios we can extend our gaze to take in longer-term opportunities and risks and thus to integrate our activities more closely. Good scenarios are plausible, but at the same time also novel and challenging. They open up new perspectives.

(…) [S]cenarios are not about predicting the future. Apart from anything else, the fact that there are several possible scenarios for every question distinguishes them from forecasting. Scenarios also differ from utopias, which are usually played out in ‘a distant land at some indeterminate time’. This is because scenarios take the present day into account, as well as the path dependencies that go with it and thus establish a clear link to the present situation. They lie somewhere between what we already know about the future in all probability and what is still entirely unknown.Instead of giving an unambiguous answer to the question about the future, like a forecast, key uncertainties are identified. What factors will exert a decisive influence, even though today we can scarcely imagine how they will turn out in the future. Which causal connections could bring about one development or another? What would be the relevant effects in that case? An important aspect of all this is that one is almost compelled to think about what really counts with regard to the underlying question. After all, we have to simplify reality in order to be able to act. The question is, therefore, what do we take into account and what do we leave out? It is not a matter of completeness but of relevance – and that means of our mental models, with which we (unconsciously) explain the world. By tackling these questions intensively various theories arise concerning the fundamental alternatives harboured by the future.

The scenarios arising from this approach illustrate the development alternatives we have identified, with their respective challenges. This is for the purpose of exploration, sounding out and evaluation. (…) Scenarios help us to pass from passive mode – ‘hopefully nothing terrible will happen’ – to an attitude that puts room to manoeuvre centre-stage: what are our options if this or that happens? Or: what can we do to promote or hinder this development?

In the scenario overview a frame of reference therefore emerges, a ‘time map’, which also serves to enable constructive exchange with others. Communication with and about scenarios is also favoured by the fact that it generally involves stories that address not only our analytical understanding but our emotions. Scenarios are multi-layered and ambiguous and have both light and shade – like real life. Scenarios can easily be distributed; people pass them on. You can read more here.

There are many other ways how stories can be utilised for critical thinking and self-reflection. A lot of the material explaining these methods is readily available online. For example, Margret Steixner uses storytelling for self-reflection in a format called story harvesting, a method developed by the „Art of Hosting Community.“ Frigga Haug has made a guide to Collective Memory-Work accessible, and Robert Hamm provides a detailed description (and discussion) of the use of Collective Memory-Work in training courses for educators.

Last not least we have also made available a documentation of the REFAK-seminars on the topic of „storytelling.“

Authors: Ulli Lipp; Philip Taucher

Read original article in German.

Lust auf mehr? Zu allen Einträgen der Serie #mm kommst du HIER!

Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung-NichtKommerziell-Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen unter gleichen Bedingungen 3.0 Österreich Lizenz.

Volltext der Lizenz